Did Most Babies Die at Birth in 50s

Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Healthier Mothers and Babies

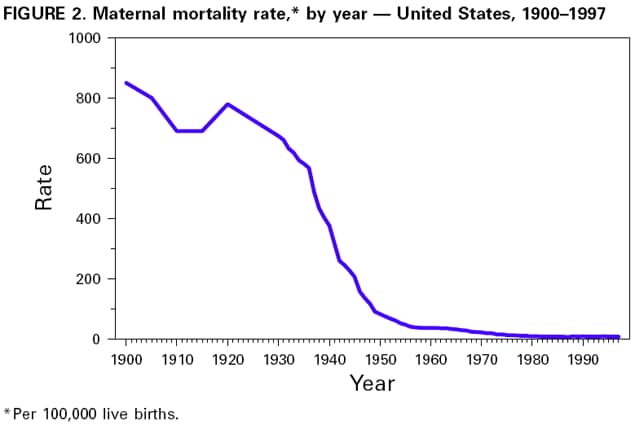

At the beginning of the 20th century, for every 1000 alive births, half dozen to nine women in the United States died of pregnancy-related complications, and approximately 100 infants died before historic period 1 year (one,2). From 1915 through 1997, the infant mortality charge per unit declined greater than 90% to seven.ii per g live births, and from 1900 through 1997, the maternal bloodshed charge per unit declined nigh 99% to less than 0.ane reported expiry per chiliad live births (7.7 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1997) (3) (Effigy one and Figure 2). Environmental interventions, improvements in nutrition, advances in clinical medicine, improvements in access to health care, improvements in surveillance and monitoring of disease, increases in education levels, and improvements in standards of living contributed to this remarkable decline (1). Despite these improvements in maternal and babe bloodshed rates, significant disparities by race and ethnicity persist. This report summarizes trends in reducing infant and maternal mortality in the United States, factors contributing to these trends, challenges in reducing infant and maternal bloodshed, and provides suggestions for public health action for the 21st century.

Infant Bloodshed

The turn down in babe bloodshed is unparalleled by other mortality reduction this century. If plow-of-the-century infant death rates had continued, then an estimated 500,000 live-born infants during 1997 would have died before age 1 yr; instead, 28,045 infants died (three).

In 1900 in some U.Due south. cities, up to 30% of infants died earlier reaching their commencement altogether (ane). Efforts to reduce infant mortality focused on improving environmental and living conditions in urban areas (1). Urban environmental interventions (e.g., sewage and refuse disposal and condom drinking h2o) played fundamental roles in reducing infant bloodshed. Rising standards of living, including improvements in economical and education levels of families, helped to promote health. Failing fertility rates also contributed to reductions in baby mortality through longer spacing of children, smaller family size, and better nutritional status of mothers and infants (1). Milk pasteurization, kickoff adopted in Chicago in 1908, contributed to the command of milkborne diseases (eastward.g., gastrointestinal infections) from contaminated milk supplies.

During the first three decades of the century, public health, social welfare, and clinical medicine (pediatrics and obstetrics) collaborated to combat babe mortality (1). This partnership began with milk hygiene but later included other public health bug. In 1912, the Children'due south Bureau was formed and became the main government bureau to work toward improving maternal and babe welfare until 1946, when its role in maternal and child health diminished; the bureau was eliminated in 1969 (1). A proponent of the Children's Agency was Martha May Eliot (see box, page 851). The Children'due south Bureau defined the problem of infant mortality and shaped the contend over programs to ameliorate the problem. The agency besides advocated comprehensive maternal and infant welfare services, including prenatal, natal, and postpartum home visits past health-intendance providers. By the 1920s, the integration of these services changed the approach to infant mortality from one that addressed infant wellness bug to an approach that included infant and female parent and prenatal-care programs to educate, monitor, and care for pregnant women.

The discovery and widespread utilize of antimicrobial agents (e.g., sulfonamide in 1937 and penicillin in the 1940s) and the development of fluid and electrolyte replacement therapy and safe blood transfusions accelerated the declines in baby mortality; from 1930 through 1949, mortality rates declined 52% (4). The percentage pass up in postneonatal (age 28-364 days) bloodshed (66%) was greater than the pass up in neonatal (age 0-27 days) mortality (forty%). From 1950 through 1964, infant mortality declined more slowly (1). An increasing proportion of infant deaths were attributed to perinatal causes and occurred amid high-chance neonates, especially low birth weight (LBW) and preterm babies. Although no reliable information be, the rapid pass up in infant mortality during before decades probably was not influenced by decreases in LBW rates considering the subtract in mortality was primarily in postneonatal deaths that are less influenced past birthweight. Inadequate programs during the 1950s-1960s to reduce deaths amidst high-take chances neonates led to renewed efforts to improve access to prenatal care, particularly for the poor, and to a concentrated effort to establish neonatal intensive-care units and to promote inquiry in maternal and infant health, including research into technologies to meliorate the survival of LBW and preterm babies.

During the late 1960s, later on Medicaid and other federal programs were implemented, infant mortality (primarily postneonatal mortality) declined essentially (five). From 1970 to 1979, neonatal bloodshed plummeted 41% (Table 1) considering of technologic advances in neonatal medicine and in the regionalization of perinatal services; postneonatal mortality declined 14%. During the early on to mid-1980s, the downward trend in U.Southward. infant mortality slowed (vi). Nevertheless, during 1989-1991, infant mortality declined slightly faster, probably because of the employ of bogus pulmonary surfactant to foreclose and treat respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants (7). During 1991-1997, baby bloodshed connected to reject primarily because of decreases in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other causes.

Although improvements in medical care were the master forcefulness for declines in baby mortality during the second half of the century, public wellness actions played a role. During the 1990s, a greater than 50% decline in SIDS rates (attributed to the recommendation that infants exist placed to sleep on their backs) has helped to reduce the overall babe mortality rate (8). The reduction in vaccine-preventable diseases (e.m., diphtheria, tetanus, measles, poliomyelitis, and Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis) has reduced infant morbidity and has had a modest effect on babe mortality (9). Advances in prenatal diagnosis of astringent fundamental nervous system defects, selective termination of affected pregnancies, and improved surgical treatment and management of other structural anomalies take helped reduce baby mortality attributed to these birth defects (10,11). National efforts to encourage reproductive-aged women to swallow foods or supplements containing folic acid could reduce the incidence of neural tube defects by half (12).

Maternal Mortality

Maternal mortality rates were highest in this century during 1900-1930 (2). Poor obstetric education and delivery practices were mainly responsible for the high numbers of maternal deaths, most of which were preventable (2). Obstetrics as a speciality was shunned past many physicians, and obstetric care was provided past poorly trained or untrained medical practitioners. Most births occurred at home with the assist of midwives or general practitioners. Inappropriate and excessive surgical and obstetric interventions (eastward.m., induction of labor, utilize of forceps, episiotomy, and cesarean deliveries) were common and increased during the 1920s. Deliveries, including some surgical interventions, were performed without following the principles of asepsis. As a issue, 40% of maternal deaths were acquired by sepsis (one-half post-obit delivery and one-half associated with illegally induced abortion) with the remaining deaths primarily attributed to hemorrhage and toxemia (2).

The 1933 White Firm Briefing on Child Health Protection, Fetal, Newborn, and Maternal Bloodshed and Morbidity written report (thirteen) demonstrated the link between poor aseptic practice, excessive operative deliveries, and high maternal mortality. This and earlier reports focused attention on the state of maternal health and led to calls for action by state medical associations (xiii). During the 1930s-1940s, hospital and state maternal bloodshed review committees were established. During the ensuing years, institutional practise guidelines and guidelines defining md qualifications needed for hospital delivery privileges were developed. At the same time, a shift from dwelling house to hospital deliveries was occurring throughout the country; during 1938-1948, the proportion of infants built-in in hospitals increased from 55% to 90% (14). However, this shift was tedious in rural areas and southern states. Safer deliveries in hospitals under hygienic weather condition and improved provision of maternal treat the poor by states or voluntary organizations led to decreases in maternal mortality after 1930. Medical advances (including the use of antibiotics, oxytocin to induce labor, and safety blood transfusion and better direction of hypertensive conditions during pregnancy) accelerated declines in maternal mortality. During 1939-1948, maternal bloodshed decreased by 71% (xiv). The legalization of induced abortion kickoff in the 1960s contributed to an 89% decline in deaths from septic illegal abortions (fifteen) during 1950-1973.

Since 1982, maternal bloodshed has non declined (16). Still, more than half of maternal deaths can be prevented with existing interventions (17). In 1997, 327 maternal deaths were reported based on data on death certificates; still, death certificate data underestimate these deaths, and the actual numbers are ii to three times greater. The leading causes of maternal decease are hemorrhage, including hemorrhage associated with ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension (toxemia), and embolism (17).

Challenges for the 21st Century

Despite the dramatic decline in infant and maternal mortality during the 20th century, challenges remain. Possibly the greatest is the persistent difference in maternal and baby health amongst diverse racial/indigenous groups, particularly between black and white women and infants. Although overall rates accept plummeted, black infants are more than twice as likely to dice as white infants; this ratio has increased in recent decades. The higher risk for babe mortality among blacks compared with whites is attributed to higher LBW incidence and preterm births and to a college hazard for death amidst normal birthweight infants (greater than or equal to 5 lbs, 8 oz [greater than or equal to 2500 yard]) (18). American Indian/ Alaska Native infants have higher death rates than white infants because of college SIDS rates. Hispanics of Puerto Rican origin take college decease rates than white infants because of higher LBW rates (19). The gap in maternal mortality between black and white women has increased since the early 1900s. During the beginning decades of the 20th century, black women were twice equally likely to dice of pregnancy-related complications as white women. Today, black women are more than than three times every bit likely to die as white women.

During the last few decades, the primal reason for the decline in neonatal mortality has been the improved rates of survival among LBW babies, not the reduction in the incidence of LBW. The long-term effects of LBW include neurologic disorders, learning disabilities, and delayed development (twenty). During the 1990s, the increased employ of assisted reproductive technology has led to an increment in multiple gestations and a concomitant increase in the preterm commitment and LBW rates (21). Therefore, in the coming decades, public health programs will need to address the ii leading causes of infant mortality: deaths related to LBW and preterm births and built anomalies. Additional substantial decline in neonatal mortality will require effective strategies to reduce LBW and preterm births. This volition be particularly important in reducing racial/indigenous disparities in the health of infants.

Approximately half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, including approximately three quarters amongst women aged less than 20 years. Unintended pregnancy is associated with increased morbidity and bloodshed for the mother and baby. Lifestyle factors (east.chiliad., smoking, drinking booze, unsafe sex activity practices, and poor nutrition) and inadequate intake of foods containing folic acid pose serious health hazards to the mother and fetus and are more common among women with unintended pregnancies. In addition, one fifth of all pregnant women and approximately half of women with unintended pregnancies exercise not commencement prenatal care during the first trimester. Effective strategies to reduce unintended pregnancy, to eliminate exposure to unhealthy lifestyle factors, and to ensure that all women begin prenatal care early are important challenges for the side by side century.

Compared with the 1970s, the 1980s and 1990s accept seen a lack of turn down in maternal mortality and a slower charge per unit of turn down in infant mortality. Some experts consider that the Usa may be approaching an irreducible minimum in these areas. However, three factors indicate that this is unlikely. Starting time, scientists have believed that infant and maternal mortality was as depression equally possible at other times during the century, when the rates were much higher than they are now. Second, the United states of america has higher maternal and infant mortality rates than other adult countries; information technology ranks 25th in infant mortality (22) and 21st in maternal mortality (23). Third, most of the U.S. population has infant and maternal mortality rates substantially lower than some racial/ethnic subgroups, and no definable biologic reason has been found to point that a minimum has been reached.

To develop constructive strategies for the 21st century, studies of the underlying factors that contribute to morbidity and mortality should be conducted. These studies should include efforts to understand not only the biologic factors merely as well the social, economic, psychological, and ecology factors that contribute to maternal and infant deaths. Researchers are examining "fetal programming"--the upshot of uterine environment (east.g., maternal stress, diet, and infection) on fetal evolution and its effect on health from babyhood to machismo. Because reproductive tract infections (e.g., bacterial vaginosis) are associated with preterm nascency, evolution of constructive screening and treatment strategies may reduce preterm births. Example reviews or audits are beingness used increasingly to investigate fetal, infant, and maternal deaths; they focus on identifying preventable deaths such as those resulting from health-care system failures and gaps in quality of care and in admission to care. Another strategy is to study cases of severe morbidity in which the woman or infant did not dice. More clinically focused than reviews or audits, such "near miss" studies may explicate why one woman or infant with a serious problem died while another survived.

A thorough review of the quality of health care and access to care for all women and infants is needed to avoid preventable bloodshed and morbidity and to develop public health programs that can eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in wellness. Preconception health services for all women of childbearing historic period, including healthy women who intend to become significant, and quality care during pregnancy, commitment, and the postpartum period are disquisitional elements needed to improve maternal and infant outcomes (run into box, folio 856).

Reported by: Division of Reproductive Health, National Middle for Chronic Disease Prevention and Wellness Promotion, CDC.

References

- Meckel RA. Salve the babies: American public wellness reform and the prevention of baby mortality, 1850-1929. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Academy Press, 1990.

- Loudon I. Death in childbirth: an international written report of maternal care and maternal mortality, 1800-1950. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Hoyert DL, Kochanek KD, Irish potato SL. Deaths: last data for 1997. Hyattsville, Maryland: U.s.a. Section of Wellness and Man Services, CDC, National Centre for Health Statistics, 1999. (National vital statistics report; vol 47, no. 20).

- Public Health Service. Vital statistics of the United States, 1950. Vol I. Washington, DC: Usa Section of Health and Homo Services, Public Health Service, 1954:258-ix.

- Pharoah POD, Morris JN. Postneonatal mortality. Epidemiol Rev 1979;i:170-83.

- Kleinman JC. The slowdown in the babe mortality decline. Pediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1990;4:373-81.

- Schoendorf KC, Kiely JL. Birth weight and age-specific assay of the 1990 Us infant mortality drop: was information technology surfactant? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151:129-34.

- Willinger K, Hoffman H, Wu K, et al. Factors associated with the transition to not-prone sleep positions of infants in the The states: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA 1998;280:329-39.

- CDC. Condition written report on the Childhood Immunization Initiative: reported cases of selected vaccine-preventable diseases--United States, 1996. MMWR 1997;46:667-71.

- CDC. Trends in babe mortality attributable to nascency defects--United States, 1980-1995. MMWR 1998;47:773-7.

- Montana E, Khoury MJ, Cragan JD, et al. Trends and outcomes later on prenatal diagnosis of congenital cardiac malformations past fetal echocardiography in a well defined nativity population, Atlanta, Georgia, 1990-1994. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:1805-ix.

- Johnston RB Jr. Folic acid: new dimensions of an old friendship. In: Advances in pediatrics. Vol 44. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby-Year Book, 1997.

- Wertz RW, Wertz DC. Lying-in: a history of childbirth in America. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Children's Bureau. Changes in infant, childhood, and maternal mortality over the decade of 1939-1948: a graphic analysis. Washington, DC: Children's Bureau, Social Security Administration, 1950.

- National Center for Wellness Statistics. Vital statistics of the The states, 1973. Vol Ii, mortality, part A. Rockville, Maryland: US Section of Wellness, Education, and Welfare, 1977.

- CDC. Maternal bloodshed--United States, 1982-1996. MMWR 1999;47:705-7.

- Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the Us, 1987-1990. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:161-7.

- Iyasu S, Becerra JE, Rowley DL, Hogue CJR. Impact of very low birthweight on the black-white infant mortality gap. Am J Prev Med 1992;viii:271-7.

- MacDorman MF, Atkinson JO. Infant mortality statistics from the 1997 menses linked birth/babe death data set. Hyattsville, Maryland: U.s.a. Department of Health and Human being Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, 1999. (National vital statistics reports, vol 47, no. 23).

- McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med 1985;312:lxxx-90.

- CDC. Touch of multiple births on low birthweight--Massachusetts, 1989-1996. MMWR 1999;48:289-92.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, Us, 1998, with socioeconomic status and health chart volume. Hyattsville, Maryland: U.s.a. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Wellness Statistics, 1998; DHHS publication no. (PHS)98-1232.

- World Wellness Arrangement. WHO revised 1990 estimates of maternal mortality: a new approach by WHO and UNICEF. Geneva, Switzerland: Earth Wellness Organization, 1996; report no. WHO/FRH/MSM/96.11.

Tabular array ane

To print large tables and graphs users may accept to modify their printer settings to landscape and apply a pocket-sized font size.TABLE 1. Percentage reduction in infant, neonatal, and postneonatal mortality, by year -- United States, 1915-1997*

| Percent reduction in mortality | |||

| Year | Infant (aged 0-364 days) | Neonatal (aged 0-27 days) | Postneonatal (aged 28-364 days) |

| 1915-1919 | 13% | 7% | 19% |

| 1920-1929 | 21% | 11% | 31% |

| 1930-1939 | 26% | eighteen% | 35% |

| 1940-1949 | 33% | 26% | 46% |

| 1950-1959 | 10% | 7% | 15% |

| 1960-1969 | 20% | 17% | 27% |

| 1970-1979 | 35% | 41% | 14% |

| 1980-1989 | 22% | 27% | 12% |

| 1990-1997 | 22% | 17% | 29% |

| 1915-1997 | 93% | 89% | 96% |

* Percentage reduction is calculated as the reduction from the first year of the fourth dimension menstruum to the terminal twelvemonth of the time period.

Return to top.

Figure 1

Return to top.

Figure 2

Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in graphic symbol translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML certificate, simply are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper re-create for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper re-create of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.Due south. Authorities Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.Page converted: ix/30/1999

This page final reviewed v/2/01

hernandezpaind1973.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4838a2.htm

0 Response to "Did Most Babies Die at Birth in 50s"

Post a Comment